The readings and discussion this week covered a lot of different topics surrounding evil. One of the ones that stood out to me is the topic of revenge. Baumeister covers a lot of other reasons that people commit evil acts without believing themselves to be evil, and revenge is one of the more understandable reasons for evil. There’s a question of how whether revenge is evil if it’s a retaliation to an evil act that’s already been committed, and according to Baumeister, the answer is often ‘yes’. Because of the magnitude gap, victims believe that the act committed against them is more serious than the perpetrator would think it was. Because of this an act of revenge may seem to be less than or equal to the original act according the person seeking revenge, but to the recipient and even witnesses, it can be considered overkill. This in turn can lead to the original perpetrator seeking revenge to “even the score”, leading to a downward spiral of increasingly ‘evil’ acts. Other times an act of revenge can be drastic but not give the satisfaction that the victim was hoping to receive.

A study on revenge was done to compare real life examples of revenge to lab-based experiments where participants are given the opportunity to exact revenge on someone – usually a confederate – immediately after they’re wronged. The study asked a large group of participants if they had ever exacted revenge and included only those who had done so. About 37% of the participants admitted to having committed acts of revenge on others. They asked these people how severe the initial act and the act of revenge was. They also recorded what domain the original act was in, and what domain the act of revenge was in, such as social exclusion, lying, violence, and infidelity. They also asked how planned the act of revenge was, and how long the gap was between the initial act and the act of revenge. They found that only 14% of people exacted revenge immediately after the act, while 64% waited for more than a day, and 48% waited longer than a week. Those who took longer did more planning with their act of revenge. The majority of participants rated their act of revenge as less severe than the initial act against them, which only supports the magnitude gap, since these accounts are self-report of the person seeking revenge and is therefore biased. They also found that only 28% of participants committed an act of revenge in the same domain as the initial act. This is important because it’s hard to consider whether an act of revenge is equal when it occurs in a different domain or context than the original act, making it more likely that the other person will see this as unfair.

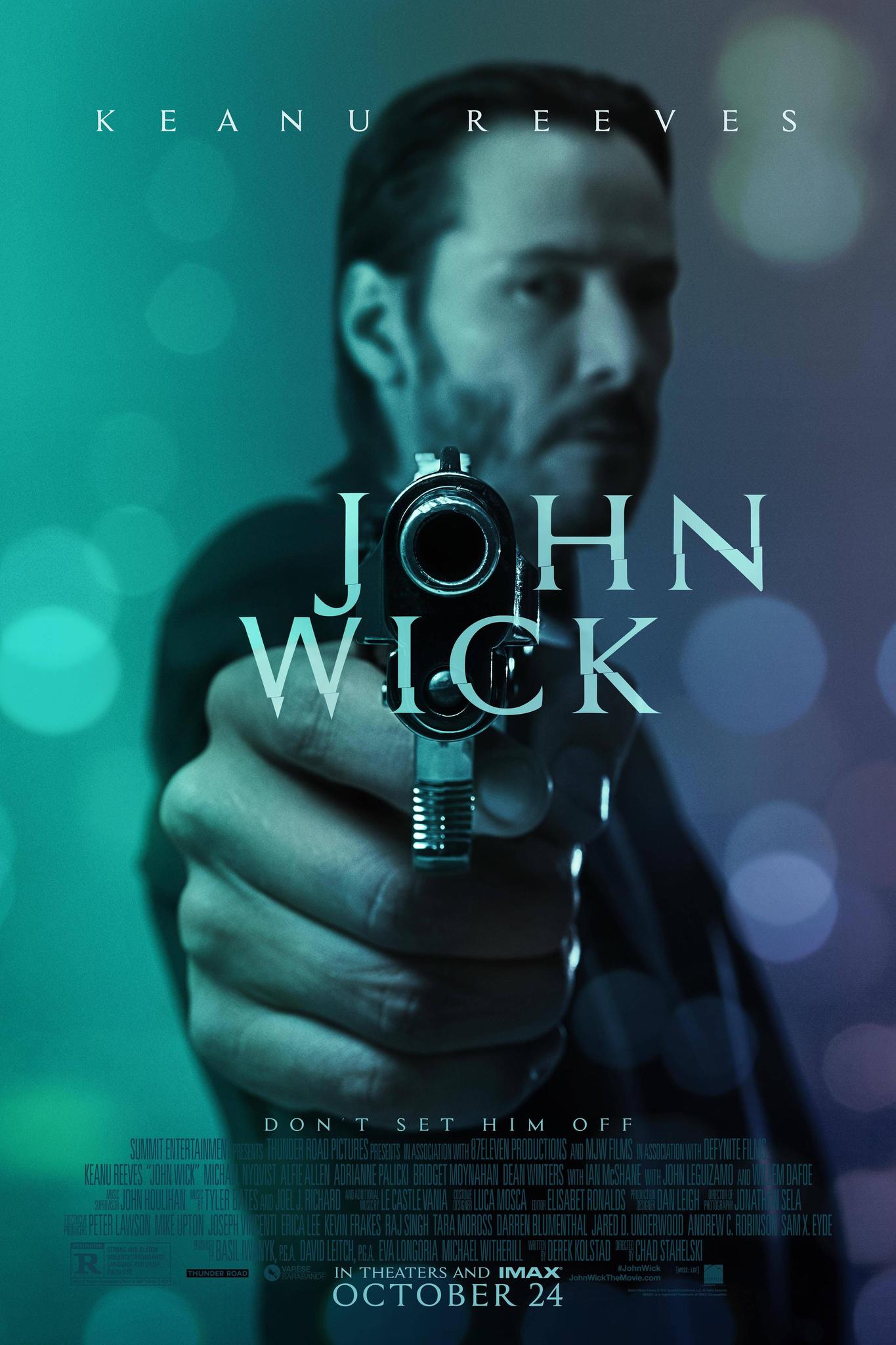

It’s interesting that revenge usually ends so badly, but much of our culture and media centers around the idea of revenge. So many movies, tv shows, books and even songs center around revenge. For example, a good portion of action movies are based on revenge. John Wick is an entire movie series that focus on revenge or punishment, even if it means killing people indirectly involved, and many characters in popular TV shows like Game of Thrones are motivated by revenge. Arya is one such example, who spends most of the show either getting revenge or training so that she can seek vengeance more efficiently. She’s seen as a strong female character and even a hero even when she does finally cross one of the names off her ever-growing list of enemies to seek vengeance against, usually through violence. It’s questionable why we’re able to root for characters even when they kill or harm others in a way that would give them the label of ‘evil’ if the act was done in isolation. We use our empathy to condone this revenge even when it turns the target of revenge into an “other” who is unforgivable and falls into our idea of pure evil. The media seems to love revenge, even if the facts behind revenge show that it’s rarely ever the proper solution.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63716550/0b7ef878f7a889788a0994907b5d7e67ab7a6851c85696f09c7d95f475347609817a905827ef64f6c15f40cab5351193.0.jpg)

Elshout, M.E. Nelissen R.M.A., van Beest, I., Elshout, S., & can Djik, W.W. (2019). Real-life revenge may not effectively deter norm violations. The Journal of Social Psychology.

Hello Hailey, thanks for your post! The topic that stood out to me the most as well was revenge. I didn’t have a full understanding of the magnitude gap before this, I think you explained that very well and furthered my understanding. I find it interesting that the study you covered only had 37% of people admitting to committing acts of revenge. I would have thought the number would be much higher. I liked how the results supported the magnitude gap, this seems like a really good study.

When I thought of media initially, I did not think about songs, I like how you mentioned that. A lot of song do involve revenge, great point! I haven’t seen game of thrones but this sounds like a great example! I look forward to discussing more in the future!

LikeLike

Hi Hailey! I too thought that 37% should be higher. But I wonder if that’s because people only attribute revenge to certain acts. For example, someone might key another person’s car if they cut them off or stole their parking spot. This would be a familiar case of revenge, but what about something smaller, like gossiping about someone who started a rumour about you? I think most people tend not to think about something like this being revenge, especially how it is portrayed in the media, like you mentioned. I think this might be why the number was a little lower than we perhaps expected. The participants might not have thought about smaller scales of revenge because it’s not used to what they see.

LikeLike

Hey Hailey! That was a very interesting study. I really found it amusing how only 28 percent of the participants committed an act of revenge in the same domain as the one where they felt they were wronged. While you mentioned that the study states that doing this makes it likely that the other person will see this as unfair and it is harder to measure how equal the two acts of evil are, I want to go out on a limb here and say that this is probably because of the perceived harm that the person taking revenge thinks will occur. For example, if you were to burn my diary that I loved writing in for years, I might go ahead and think of the object you love the most, and in this case let’s say it is your car. I would then want to do something to your cherished object, as you did mine, and proceed to key your brand new car. While a third person may say that the car is much more monetarily valuable than my burned diary, you could also make the argument that my diary was immensely, if not more valuable, in terms of personal value, emotions, and memories that I stored on it. After all, if you had a diary but you barely cared for, me burning it would not make the anticipated harm on you as equal to the harm that I felt when you burned my diary.

LikeLike